Jacob The Refugee

19/11/15 15:36 Filed in: Torah

When we last left Jacob, our hero (or, perhaps, antihero) he had just manipulated his brother, Esau, out of his birthright. Not long after that, also in last week’s Torah portion, Jacob would flat out lie to and deceive his father, Isaac – who is old and blind. Why the deception? In order to receive the sacred, deathbed blessing that his father had intended for Esau, who was Isaac’s favorite son. (Putting the “fun” in “dysfunctional,” as I like to say, it is Jacob’s mother, Rebecca, who masterminds the ruse that her favorite son, Jacob, uses to fool her husband, Isaac.)

Rebecca overhears Esau swearing that he will kill Jacob as soon as their father, Isaac, is gone. She urges Jacob to flee to Haran, her birthplace, until Esau has cooled down. She says, somewhat ominously, “Let me not lose both of you in the same day.” It’s not clear whether “both of you” refers to Jacob and Esau or, perhaps, to Jacob and Isaac, who “broke into violent trembling” when he realized that he had blessed “the wrong” son.

There are times when it’s not so easy to draw connections between a particular Torah portion and what’s going on in our world, or in our own lives. And there are times when the connections, the “relevance,” fairly grabs us by the shoulders and shakes us. I find this to be the case with this week’s portion, Vayetze.

At this moment of his life, fleeing his home in Canaan and fearing for his very life, Jacob is, unmistakably, a refugee. But, his situation is different from that of so many who flee their homes and families.

First, of course, you could argue that Jacob’s refugee status is of his own making. He has brought Esau’s hostility upon himself through his own overreaching ambition. The Torah foreshadows this aspect of Jacob’s personality when it explains that his name derives from the Hebrew word “ekev,” meaning “heel.” Jacob is always looking to trip up the person whom he perceives to be standing in his way, even as he is born holding on to the heel of Esau. It will take some twenty years of being himself a victim of trickery and mistrust until a much humbler Jacob wrestles with a mysterious stranger (his conscience?) and is given the name “Israel,” which might mean something like, the one who struggles and in the process becomes “upright.”

Jacob’s refugee status is also different from that of the typical refugee in that he has a definite destination. The Torah portion begins with the words, “Jacob went out from Beersheba and journeyed toward Haran.” Sometimes we are like Abraham, whom God simply instructs to “get going… to [an unspecified] land that I will show you.” In this, I am reminded of lyrics from a favorite James Taylor song: “It’s enough to be on your way / It’s enough just to cover ground…” Indeed, it is the plight of a more typical refugee to run from a situation that is dangerous, toxic, intolerable, but often this person has no idea where the journey will lead. “Vayetze,” the need to leave, is clear. “Vayelekh,” the need for a destination, is a luxury that will be fulfilled much later.

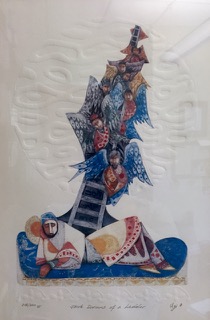

Finally, Jacob is different than the typical refugee in that he’s been given ironclad reassurance from God that everything will turn out all right. He falls asleep and has his famous dream: he is at the foot of an enormous ladder, or ramp, planted on the ground and extending up into the sky. Angels “ascend and descend” on the ladder. God appears to him and tells him that God will not leave him while he is on his journey. Jacob learns that he has a destiny.

Is it “a stretch” to think about the refugees streaming out of Syria at this very moment in the light of Jacob’s story? Unlike Jacob, they do not have a predetermined destination, nor is their predicament a consequence of their own misbehavior, but rather of a brutal dictator and of political and religious extremism on a scale that is difficult to grasp, even as we follow the news.

When Jacob awakens from his dream, he exclaims, “Surely God was in this place all along, and I did not know it.” How is God to be manifested in the lives of innocent human beings longing for freedom and safety? How is God to be manifested in the response of the nations of the West?

Have you ever had to leave a place against your will? How did that feel? Where did you find strength and support in such a situation?

I welcome your comments!

Shabbat Shalom,

Rabbi Steve Folberg

blog comments powered by Disqus